Dark Matter vs MOND: A Comparative Overview

Abstract

The purpose of this post is to present a comparative overview of the dark matter hypothesis and its leading competitor: Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND). An abridged history of the subject is given, as is a description of the observations and theoretical problems which motivated these hypotheses, and of how they purport to resolve these problems. Criticisms and countercriticisms of each are considered within the context of the formal scientific literature.

Introduction:

What’s the Problem? Many observations in modern astronomy and cosmology suggest dynamic behavior which cannot easily be reconciled with our current understanding of gravitational dynamics without hypothesizing the presence of additional matter beyond what can currently be directly detected (CERN, Garrett and Duda 2011). This hypothetical missing mass has come to be known as dark matter because it does not appear to interact electromagnetically like ordinary (baryonic) matter. That is to say that it doesn’t absorb, emit or reflect light. Its presence is thus inferred entirely from its gravitational effects on other objects which are detectable by other means.

Moreover, in order to fit current observations, it must comprise about ~85% of the existing mass and ~26% of the total mass-energy in the universe (Garrett and Duda 2011, Caputo et al 2019, Roberts et al 2017, Bertone 2010). The justifications for the dark matter hypothesis come from many independent lines of evidence, including the rotation curves of spiral galaxies, gravitational lensing, velocity dispersions of elliptical galaxies, globular clusters, galaxy clusters, the large scale structure of the universe, and precision analyses of the power spectrum of Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) anisotropies (Corbelli and Salucci 1999, Natarajan et al 2017, Refregier 2003, Carollo et al 1995, Wu et al 1998, Zwicky 1933, Holtzman 1989).

Although garnering provisional acceptance among the majority of astronomers, cosmologists and physicists, the non-baryonic DM hypothesis is not without its caveats, criticisms and detractors (Bertone and Hooper 2018, Milgrom 1989). Namely, a type of matter satisfying the constraints placed on its properties by the observational evidence has proven elusive to non-gravitationally dependent detection methods. This has given rise to alternative hypotheses. The most prevalent of these alternatives postulate that what appears to us as evidence of a new kind of matter may in fact be a result of gravitational dynamics working differently on larger scales than locally. These are typically categorized under the umbrella of Modified Newtonian Dynamics, or MOND for short (Milgrom 1989).

Why Dark Matter?

Historically, the concept of a significant quantity of unseen matter existing has been postulated in response to very different problems. Consequently, the answer to the question of what motivated the idea has multiple answers. This treatment focuses only on permutations of the idea explicitly related to the modern dark matter hypothesis in contemporary astrophysics and cosmology.

Two major categories of early-mid to late-mid 20th century astrophysical problems were especially influential in the rise of the dark matter hypothesis: velocity dispersions in galaxy clusters, and rotation curves of individual galaxies (Bertone and Hooper 2018).

For instance, one of the most widely recognized pioneers of dark matter is Swiss-American astronomer, Fritz Zwicky, who in the early 1930s was studying the large dispersion velocities observed in the Coma cluster (Zwicky 1933). Zwicky estimated the mass and size of the cluster and used these estimates to calculate a potential energy for the cluster, from which a kinetic energy and a velocity dispersion could be computed using the virial theorem. The expected velocity dispersion he calculated was over an order of magnitude less than what had been inferred via their redshifts. For this reason, Zwicky postulated that dark matter must be present in amounts exceeding that of ordinary luminous matter, as this would explain the high dispersion velocities (Zwicky 1933). Contrary to popular belief, this was not the first usage of the term dark matter in the formal literature. In fact, it wasn’t even the first time Zwicky had used it in a paper. Moreover, his usage of the term was consistent with the manner in which it had previously been employed by Kapteyn, Oort, and Jeans (Bertone and Hooper 2018). Following up a few years later, Zwicky estimated a mass-to-light ratio for the Coma cluster that was about 500 times as high as for the Sun (Zwicky 1937). This value relied on contemporary estimates of the Hubble constant at that time, which were nearly an order of magnitude greater than the accepted value today, but even replacing it in his calculation with the modern value yields a very high mass-to-light ratio (Bertone and Hooper 2018). In contrast to the modern conception of dark matter, however, Zwicky attributed the unseen mass to “cool and cold stars, macroscopic and microscopic sold bodies, and gases” (Zwicky 1937). Sinclair Smith arrived at similar conclusions in regards to the Virgo cluster, and attributed the excess mass to internebular material, possibly consisting of massive low-luminosity clouds surrounding the galaxies (Smith 1936).

Although even Edwin Hubble himself acknowledged that these discrepancies were a problem to be solved, the astronomy community of the time were skeptical of the assumptions underlying the estimates of Zwicky and Smith. For example, it was suggested that many of the observed galaxies could be just passing through along hyperbolic orbits, but weren’t actually permanently gravitationally bound to the cluster (Holmberg 1940). Zwicky himself even questioned Smith’s assumption that the galaxies of the Virgo cluster were in equilibrium (Zwicky 1937).

Nevertheless, although the views of mid-20th century astrophysicists were varied with respect to missing matter hypotheses, the problems which motivated them, (such as high velocity dispersions and mass-to-light ratios) persisted (Schwarzschild 1954, Holmberg 1940, Burbidge 1959, Limber 1962).

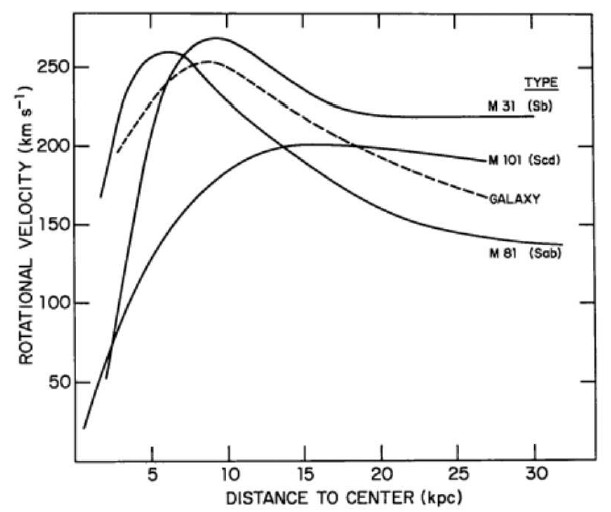

That said, the observations which ultimately persuaded the greatest number of scientists to take the DM hypothesis seriously were related not to galaxy cluster dynamics, but to the apparently flat rotation curves of individual galaxies (Bertone and Hooper 2018). Although cautious in his interpretation, Horace Babcock presented a rotation curve for the M31 (Andromeda) nebula in his 1939 PhD dissertation, which featured unexpectedly high rotation velocities at large radii (Babcock 1939). Subsequent observations and analyses were somewhat equivocal through the 40s and 50s, with prominent theorists suggesting that more recent rotation curves did not deviate sufficiently from expectations to imply anything out of the ordinary (Schwarzschild 1954, Van de Hulst 1957, Schmidt 1957).

That all began to change as radio astronomy techniques became more refined, and galactic rotation curves were observed which were at odds with the luminous matter distributions implied by signals in either the visible range or in the 21 cm lines, and for which unseen additional matter was postulated as the explanation (Freeman 1970, Rubin and Ford Jr 1970, Rogstand and Shostak 1973, Roberts and Rots 1973, Rubin 1978, Rubin 1979).

It was soon then recognized that the same idea could solve multiple problems simultaneously (Ostriker, Peebles and Yahil 1974, Faber and Gallagher 1979). By this time, cosmologists were also realizing that additional matter was required to explain certain aspects of large-scale cosmic structure formation (Gott et al 1974), as well as the large-scale anisotropies and density fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and mass distribution respectively (Peebles 1982). In the latter paper, Peebles also suggested that the missing mass could not be predominately baryonic (composed of protons and neutrons). He argued that the problem would be resolved if the universe is dominated by weakly interacting massive particles (now called WIMPS) on the grounds that this would permit small-scale density fluctuations to grow prior to decoupling, because then the observed fluctuations would have already been in place at the time the CMB was produced (Peebles 1982). Several other DM candidates have been proposed besides WIMPS, including Primordial Black Holes, Asymmetric Dark Matter, Axions and other Ultra light bosons, whose proposed properties I won’t go into here (Bozorgnia et al 2024).

From Dark Matter to ΛCDM: A Cosmological Synthesis

By the mid-1980s, all these separate lines of evidence had culminated in the widespread acceptance of the dark matter paradigm in cosmology and astrophysics (Bertone and Hooper 2018). By the early 90s, it had become an indispensable part of cosmological models, not only for galactic dynamics, but also for enabling the growth of large-scale structure from primordial density fluctuations (Blumenthal et al 1984). By 1998, however, it was discovered that the expansion rate of the universe was accelerating (Riess et al 1998). This was based on observations of Type 1a Supernovae, and motivated the revival of Einstein’s cosmological constant Λ, which he’d discarded upon learning of Hubble’s discovery that the Universe was expanding back in the 1920s, referring to it later as the greatest blunder of his career (American Physical Society News). The new discovery, which came to be known as “Dark Energy,” found a new use for the concept (albeit for a different purpose). This term is the “Λ” in “ΛCDM,” which is the result of a cosmological synthesis that integrated both Dark Matter and Dark Energy with the modern understanding of the evolution of the large-scale structure of the universe.

ΛCDM is currently the prevailing model in modern cosmology (read more about it here and here). The takeaway ideas are that ΛCDM means “lambda cold dark matter,” and it describes the evolution and large-scale structure of the universe from the Big Bang to the present, while incorporating dark energy (represented by the cosmological constant Λ) and cold dark matter, which influences the gravitational dynamics of cosmological structure. It explains phenomena such as galaxy formation, anisotropies in the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation, and observations that the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating. The reason for the “cold” dark matter qualifier is because “hot dark-matter” models (e.g. neutrinos) were abandoned upon the realization that such matter, which moves at close to the speed of light, wouldn’t allow for the early formation of smaller-scale clumping to form galaxies. It could only form larger-scale superclusters, and that would contradict observations indicating that early galaxy formation preceded the build up to the currently-observed cosmic web. The nearly light-speed hot dark matter candidates would create a streaming effect that would effectively wash out the small density fluctuations in the early universe that lead to this outcome (Primack 2001).

Problems of the ΛCDM Paradigm and the Emergence of MOND

As of this writing, no direct detection of dark matter has been reported, thus despite vigilant observational efforts and theoretical work, its precise identity remains conjectural. What’s known are merely constraints on the properties it must possess. We know it doesn’t interact electromagnetically, only gravitationally (and possibly also via the weak interaction). It was thought for a time that black holes and Massive Compact Halo Objects (MACHOs) might account for it, but further investigation revealed that these could comprise a tiny percentage of the DM at most (Alcock et al 2000). Although scalar field dark matter candidates such as axions have also been proposed, the most prevalent hypothesis for the identity of the DM describes them as Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) (Jungman et al 1995, Kamionowski 1997, Bergstrom 2000). Modern particle physics theories such as Supersymmetry (SUSY) which strive to move beyond the Standard Model of particle physics predict supersymmetric partners to the elementary particles of the Standard Model, and some of them are predicted to possess properties consistent with the WIMP DM paradigm (Jungman et al 1995, Feng et al 2000). However, persistent attempts to detect such particles have consistently fallen short (Strigari 2013, CMS collaboration 2017, Allen 2018).

One of the overriding assumptions of the dark matter hypothesis is that gravitational dynamics work the same way over large distances as they do in the shorter-scale regimes in which their consistency and reliability has been established. Naturally, this means that alternative explanations become possible if that assumption is relaxed. That’s exactly what has been done by researchers seeking alternative explanations for these observations which don’t rely on the presence of large quantities of a hitherto unknown type of matter. This has been accomplished by supplanting Newtonian Dynamics and General Relativity at low accelerations with models in which gravitational acceleration falls off less sharply with distance at low accelerations (Milgrom 2019). Approaches of this sort have come to be known as Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND). In the early 1980s, Mordehai Milgrom published three papers in which he took the asymptotic flatness of galactic rotation curves at large r to be an axiomatic requirement of the MOND paradigm (Milgrom 1983a, Milgrom 1983b, Milgrom 1983c). The term paradigm is appropriate here, because MOND is neither a complete scientific theory nor a single model, but rather a category of related frameworks which converge with the predictions of Newton and of GR in the weak-field limit (Milgrom 2019).

In Milgrom’s original formulation, there was some ambiguity as to whether it should be interpreted as a modification of gravity or of Newton’s 2nd law, and it is not uncommon for both types of ideas to be lumped into the MOND category due to their common goals.

For example, in the first of his 1983 papers, Milgrom introduced the relation 𝑚gμ(𝑥)(𝑎/𝑎𝑜)a = F, where a is the magnitude of the acceleration vector a, mg is the gravitational mass, F is the force, ao is a new fundamental constant, and is a function with the property that μ(𝑥) → x for x << 1, and μ(𝑥) → 1 for x >> 1. This can be understood as a correction to Newton’s F = ma, but with the source term F still proportional the gravitational mass and still deduced in the conventional way from the mass distribution. Here, the distinguishing feature is that the inertial force is no longer proportional to the acceleration in the limit of small accelerations. However, in his follow-up papers in which he demonstrates how MOND can account for mass-to-light ratios and various gravitational dynamics problems, he deals exclusively with gravitational systems and employs a weaker set of assumptions. Namely, he concedes that the modification needn’t necessarily apply to accelerations from other forces, in which case his modification could be considered one of gravity, not the law of inertia (Milgrom 1983a, Milgrom 1983b, Milgrom 1983c). As Milgrom himself was quick to point out, his model was no more than an effective working formula describing weak-field limit behavior, and was not to be construed as a complete scientific theory. The essential point here is that MOND describes an entire family of physics ideas which can be based on either modified inertia or modified gravity. However, embedding these within a more comprehensive and realistic theoretical framework has proven difficult (Bertone and Hooper 2018). In fact, his original formalism conserved neither energy, momentum, nor angular momentum. There have been many attempts to reformulate MOND and/or incorporate it into a broader theories (both relativistic and non-relativistic), and the current treatment is not intended as a comprehensive breakdown of its variations (Milgrom 2014, Bertone and Hooper 2018). Rather, different variations are introduced here as needed for the purpose of comparing their predictions with those of appropriate DM formulations for the same observational phenomena.

In the following section we examine the ways in which these two competing frameworks (dark matter vs MOND) account for the observations of interest.

Galactic Rotation Curves

As mentioned previously, one of the most influential problems insofar as the mainstream acceptance of dark matter was the observation of nearly flat galactic rotation curves at large r.

To understand why this was a problem, we consider a spherical mass distribution with circular orbits, and define M(r) as the mass interior to some radius r. The acceleration of some star or clump of gas at radius r is ![]() which we set equal to the acceleration produced by gravity,

which we set equal to the acceleration produced by gravity, ![]() , which yields an expression for the mass interior to

, which yields an expression for the mass interior to![]() , Differentiating with respect to r, yields

, Differentiating with respect to r, yields ![]() , which by conservation of mass in a spherically symmetric system would imply

, which by conservation of mass in a spherically symmetric system would imply ![]() (Carroll and Ostlie 2014). For flat rotation curves, v remains roughly constant for large r as r increases (Garrett and Dudna 2011). This implies that the mass interior to r must be increasing with increasing r in a manner consistent with a density distribution of the form

(Carroll and Ostlie 2014). For flat rotation curves, v remains roughly constant for large r as r increases (Garrett and Dudna 2011). This implies that the mass interior to r must be increasing with increasing r in a manner consistent with a density distribution of the form ![]() ∝

∝ ![]()

![]() (Carroll and Ostlie 2014). The dark matter hypothesis makes sense of this apparent discrepancy by retaining current gravitational models and solving for the mass distributions necessary to produce those flattened curves in spiral galaxies, whereas MOND takes a distribution of luminous matter consistent with star counting methods and fits its parameters to the observed rotation curves. For example, one Milky Way cold dark matter (CDM distribution that achieved good agreement over a large range of r was

(Carroll and Ostlie 2014). The dark matter hypothesis makes sense of this apparent discrepancy by retaining current gravitational models and solving for the mass distributions necessary to produce those flattened curves in spiral galaxies, whereas MOND takes a distribution of luminous matter consistent with star counting methods and fits its parameters to the observed rotation curves. For example, one Milky Way cold dark matter (CDM distribution that achieved good agreement over a large range of r was ![]() (Navarro, Frenk, White 1996). On the other hand, MOND made predictions about low surface brightness galaxies with which subsequent observations in the 90s were shown to be compatible, which was impressive at the time, because the dynamics of such systems had previously not been well measured (McGaugh and de Blok 1997a, McGaugh and de Blok 1997b). Both approaches introduce additional problems to be solved, and the problem of galactic rotations curves does not conclusively rule out one or the other. What about galaxy clusters?

(Navarro, Frenk, White 1996). On the other hand, MOND made predictions about low surface brightness galaxies with which subsequent observations in the 90s were shown to be compatible, which was impressive at the time, because the dynamics of such systems had previously not been well measured (McGaugh and de Blok 1997a, McGaugh and de Blok 1997b). Both approaches introduce additional problems to be solved, and the problem of galactic rotations curves does not conclusively rule out one or the other. What about galaxy clusters?

Cluster Dynamics

As mentioned earlier, another area in which the DM hypothesis has been invoked is in the dynamics of galaxy clusters. To recap, members of galaxy clusters were observed to exhibit velocity dispersions that were higher than could be explained via contemporary gravitation theories without the inclusion of a significant amount of unseen matter. Astrophysicists operating under the ΛCDM paradigm have been fairly successful in using gravitational lensing to map the mass distributions of galaxy clusters needed to account for observations (Tyson et al 1990, (Broadhurst et al 1994, Massey et al 2015).

It had already been known since the late 80s that MOND could not get rid of the need for unseen matter in galaxy clusters entirely, but by the late 90s, evidence was emerging that it could substantially reduce the amount needed to explain various cluster phenomena (The and White 1988, Sanders 1997, Bekenstein 2007, Milgrom 2019). MOND proponents viewed this not as a rebuke of the paradigm but as an opportunity to use it to make a prediction. Namely, it was argued that the amount of unseen matter needed to fit the data could plausibly be accounted for by missing baryons, and thus the presence of additional baryons comparable in mass to the visible matter follows as a prediction of MOND for galaxy clusters (The and White 1988, Sanders 1997, Milgrom 2019).

Enter TeVeS

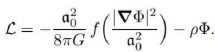

As stated earlier, there have been numerous versions of Modified Gravity, both relativistic and non-relativistic. One noteworthy relativistic formulation was developed by Jacob Bekenstein, and is known as Tensor Vector Scalar gravity (TeVeS) (Bekenstein 2004). TeVeS is a relativistic theory which reproduces Milgrom’s MOND acceleration formula in the weak field approximation and accounts for gravitational lensing. It was derived via the action principle, and can be expressed as a Lagrangian density whose ingredients include two scalar fields (one dynamical and one not), a unit vector field, and a matter Lagrangian (Bekenstein 2004). As Bekenstein explains, his formulation of TeVeS was built in part upon his previous work with Milgrom on a non-relativistic generalization of MOND commonly referred to as Aquadratic Lagrangian theory (AQUAL) (Bekenstein and Milgrom 1984, Bekenstein 2004). The AQUAL Lagrangian takes the form:

Here, a0 is the acceleration scale constant, ρ is the mass density, and f is an unspecified function of the magnitude squared of the gradient of the potential, and has the property that f(y) → y for y >> 1, and f(y) →for y << 1.

Deriving it via the action principle guaranteed the preservation of the requisite conservation laws, and AQUAL reduced to Milgrom’s original MOND force relation in spherically symmetric cases. Nevertheless, it was non-relativistic and thus couldn’t account for gravitational lensing, and his earliest attempts to “relativize” it by modifying the Einstein-Hilbert action with a conformal factor resulted in causality violations (Bekenstein and Milgrom 1984, Bekenstein 2004). TeVeS was designed to fix that. It preserves both relativistic invariance and the equivalence principle, and avoids superluminal phenomena and causality violations which had arisen in earlier formulations (Bekenstein 2004). Bekenstein combined the AQUAL idea with a modified Einstein-Hilbert action involving a metric utilizing a unit time-like 4-vector field formulated by R. H. Sanders (Sanders 1997, Bekenstein 2004, Bekenstein 2007).

A full description of the TeVeS action is beyond the scope of this paper, but it essentially takes the form of the sum of the integrals of three Lagrangians, one of which involves rank 2 tensors, another of which takes a vector form, and the remaining of which involves scalar functions (hence the name Tensor Vector Scalar theory) (Bekenstein 2004).

TeVeS has been successful in accounting for some of the galaxy cluster phenomena that its predecessors could not (Zhao 2006, Bekenstein and Sanders 2011), but some other problems have arisen as well. For example. Michael Siefert pointed out that for spherically symmetric TeVeS solutions, stars would be highly unstable (Siefert 2007).

Other researchers have concluded that TeVeS can solve either the lensing problem in clusters or the rotation curve problem in galaxies for particular choices of the parameters, but that those parameter choices are not compatible (Mavromatos et al 2009). In other words, the parameter values which minimize the DM needed in clusters don’t accurately characterize galactic rotation curves, and the parameter values which resolve the rotation curve problem still require a non-trivial amount of dark matter to fit lensing data in clusters (Mavromatos et al 2009). That said, other investigations have suggested that at least some of these problems could be alleviated if there are massive hot neutrinos on the order of 2eV (Angus et al 2006). More recently, it has been argued that gravitational wave detection data at LIGO falsify TeVeS and other MOND theories and support General Relativity (and thus Dark Matter) (Boran et al 2017).

Gravitational Lensing and the Bullet Cluster

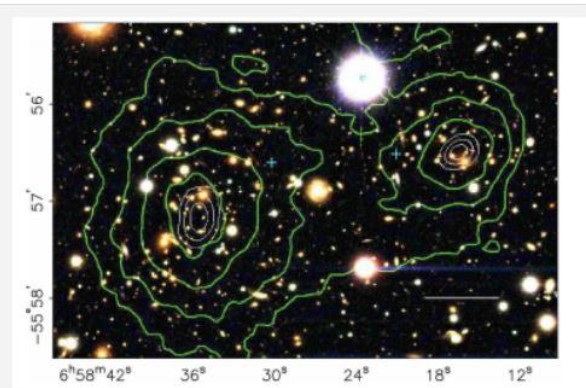

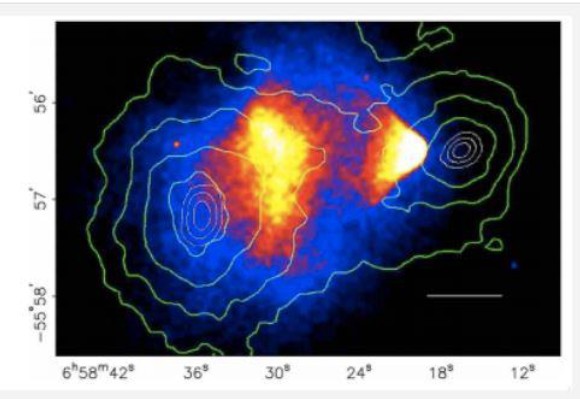

Here we arrive at what many researchers take to be one of the strongest pieces of evidence for Dark Matter to date. This evidence derives from observations of the 1E 0657-56 galaxy cluster, of which two sub-clusters underwent a rare high velocity collision event at red shift z = 0.296 (Clowe, Gonzalez and Markevitch 2003, Markevitch et al 2004). Observations in the x-ray range show a bullet-like gas sub-cluster just exiting the collision site. On the other hand, observations in the optical range show that the gas lags behind the galaxy sub-cluster, whereas weak gravitational lensing mass maps indicate dark matter clumps well ahead of the bullet-like gas sub-cluster and coincident with the centroid of the galaxies, effectively “separating” the dark matter from the baryonic gas (Clowe, Gonzalez and Markevitch 2003, Markevitch et al 2004, Clowe et al 2006)).

In the original paper by Clowe, Gonzalez and Markevitch, the constraints the observations placed on the interaction cross-section of the DM were a point of focus. By that time, the DM paradigm had already earned the provisional acceptance of most researchers in related fields. Although its significance in establishing that DM exists did not go without mention in their 2003 paper, that was not the authors’ central focus so much as inferring tighter constraints on its properties (Clowe, Gonzalez and Markevitch 2003, Markevitch et al 2004). It wasn’t until a 2006 follow-up paper that the evidence was used to build a case for a “direct empirical proof” of dark matter (Clowe et al 2006). Nevertheless, these observations have gone a long way in reinforcing confidence in Dark Matter and the ΛCDM paradigm simply because they are very difficult to account for without it (Carroll 2006).

It’s worth pointing out that the bullet cluster findings do “not rule” out MOND conclusively, but they do present additional constraints on which permutations of MOND can remain viable and are difficult to explain without invoking at least some yet undetected matter. There have been several counterpoints from critics of the standard ΛCDM interpretations of the Bullet Cluster. Some of these argue that the bullet cluster does not present any new problems with MOND that weren’t already known (and presumably reconcilable), and that those arguing otherwise have misunderstood and/or misrepresented what MOND is and isn’t purported to explain. For example, although not a formal research paper, Milgrom himself published an informal rebuttal online in which he summarized his counterarguments (Milgrom 2006). The crux of Milgrom’s argument is that the Bullet Cluster presents no more of a problem for MOND than what had already been known with respect to galaxy clusters more generally (citing Sanders 1999). He acknowledges that MOND does not fully explain the apparent virial discrepancies of cluster dynamics and emphasizes that MOND considerably reduces the amount of unseen matter needed to fit the cluster data. He goes on to argue that the amount of missing mass needed is comparable to the amount already visible, and that it could therefore still plausibly turn out to be ordinary baryonic matter (Milgrom 2006).

Other critics of Dark Matter have turned the question on its head by arguing that it is, in fact, the standard Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) cosmological model which is most imperiled by the Bullet Cluster observations, not MOND (Lee and Komatsu 2010). Lee and Komatsu performed simulations to calculate the distribution of initial in-fall velocities of galaxy sub-clusters based on a standard ΛCDM cosmological model and compared their results to the initial (pre-collision) velocities used in non-cosmological hydrodynamic simulations of the Bullet Cluster. Based on their analysis, the authors concluded that such large initial in-fall velocities would be exceedingly improbable on ΛCDM (Lee and Komatsu 2010).

Other researchers had found the relative CDM velocity to be lower than the shock-velocity (wave-front propagation speed), and had concluded that the observations are compatible with ΛCDM (albeit with some sensitive dependence on the initial mass and gas density profiles) (Hayashi 2006, Milosavljevic et al 2007). Still other critiques argued that some versions of MOND (such as TeVeS) can, in fact, account for the Bullet Cluster observations (Angus et al 2006). Most cosmologists and astrophysicists have found these rebuttals unconvincing, however, as Scott Dodleson explains in his 2011 paper in which he outlines what he takes to be a much bigger challenge for MOND (Dodleson 2011). Dodleson argues that an even bigger problem for MOND than the bullet cluster is the shape of the matter-power spectrum corresponding to acoustic oscillations observed in the CMB. He explains that in a DM-dominated universe, these matter oscillations, which are called Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO), are suppressed as baryons fall into potential wells produced by the DM during early structure formation, thus leaving only miniscule traces of the primordial matter oscillations. In contrast, Dodleson argues, these oscillations should be just as apparent in matter as they are in radiation, and even if TeVeS or generalizations thereof can fix the amplitudes, it would still not accommodate the general shape of the matter power spectrum (Dodleson 2011).

Here’s a concise comparative summary table that I generated with the help of ChatGPT:

| Category | Dark Matter (DM) | Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | ~85% of matter is invisible, interacts gravitationally but not electromagnetically. | Newton’s laws (and/or gravity) break down at very low accelerations (< a0a_0). |

| Origins | Zwicky (1930s): velocity dispersions in clusters. Rubin & Ford (1970s): flat galactic rotation curves. | Milgrom (1983): proposed new constant a0a_0, modifying dynamics to explain flat curves. |

| Key Successes | Explains: galactic rotation curves, cluster dynamics, gravitational lensing, large-scale structure, CMB anisotropies. | Predicts flat rotation curves without invisible matter; successful for low surface brightness galaxies. |

| Main Candidates | WIMPs, axions, supersymmetric particles, etc. | No particles; purely modified dynamics (though some versions require extra unseen baryons). |

| Direct Evidence | None yet, despite major experimental searches. | No need for exotic particles, but lacks a full physical theory. |

| Galaxy Rotation Curves | Requires extended dark halos (e.g., NFW profile). | Matches rotation curves from luminous matter + modified force law. |

| Galaxy Clusters | Lensing maps consistent with DM halos. | Reduces but does not eliminate missing mass—still needs unseen baryons. |

| Gravitational Lensing | Naturally explained by DM halos. | Needs relativistic extensions (e.g., TeVeS) to handle lensing. |

| Bullet Cluster | Strongly supports DM: lensing mass separated from hot baryonic gas. | Hard to explain without additional unseen matter; proponents argue issue not unique to Bullet Cluster. |

| CMB / BAO | Explains power spectrum and baryon acoustic oscillations well. | Struggles to match observed spectrum shape/amplitudes. |

| Theoretical Issues | No detected particles yet; identity unknown. | Conservation law violations in early forms; no fully consistent relativistic framework. |

| Status | Dominant paradigm in cosmology & astrophysics. | Minority view; some astrophysicists continue research. |

| Philosophical Framing | Adds new matter while keeping physics intact. | Alters fundamental laws of gravity/inertia. |

| Future Outlook | Direct detection of DM would settle the debate. | Would gain traction if DM remains undetected and MOND can extend to clusters & CMB. |

In closing

Some of the disagreements here are, at least in part, over what constitutes a more parsimonious account of the data (e.g. the heuristic of Occam’s razor). Both paradigms introduce new parameters and assumptions, but proponents of each disagree on which paradigm introduces the most or the biggest assumptions in order to fit the data. Proponents of MOND view dark matter as the luminiferous ether of our generation and view the lack of direct DM detection as evidence that our models are to blame for the aforementioned problems. ΛCDM proponents don’t find this view compelling on the grounds that the MOND alternatives also introduce new assumptions and parameters, and have no underlying physical theory, whereas DM would solve many problems simultaneously using established physical principles with the only new ancillary assumptions being the prediction of one or more new types of particles.

Dark matter is the paradigm favored by most cosmologists and astrophysicists (overwhelmingly so), but a small minority of MOND proponents continue to forge on and will likely continue to do so until direct DM detection is achieved and the detected particles shown to plausibly comprise the amount of missing mass postulated. If several more years go by without any successful direct DM detection, or if some version of MOND achieves unprecedented success, then that might change one day, but this is the current state of affairs.

References

Alcock, C., Allsman, R. A., Alves, D. R., Axelrod, T. S., Becker, A. C., Bennett, D. P., … & Geha, M. (2001). MACHO Project Limits on Black Hole Dark Matter in the 1-30 M☉ Range. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 550(2), L169.

Allen, R. E. (2018). Saving supersymmetry and dark matter WIMPs—a new kind of dark matter candidate with well-defined mass and couplings. Physica Scripta, 94(1), 014010.

Babcock, H. W. (1939). The rotation of the Andromeda Nebula. Lick Observatory Bulletin, 19, 41-51.

Bergström, L. (2000). Non-baryonic dark matter: observational evidence and detection methods. Reports on Progress in Physics, 63(5), 793.

Bertone, G. (2010). The moment of truth for WIMP dark matter. Nature, 468(7322), 389-393.

Bertone, G., & Hooper, D. (2018). History of dark matter. Reviews of Modern Physics, 90(4), 045002.

Beuke, F. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://beuke.org/lambda-cdm/#:~:text=Baryons%20can%20radiate%20energy%20(e.g.,and%20Big%20Bang%20nucleosynthesis%20calculations.

BLUMENTHAL, G. R., FABER, S., PRIMACK, J. R., & REES, M. J. (1984). FORMATION OF GALAXIES AND LARGE SCALE STRUCTURE WITH COLD DARK MATTER’.

Bozorgnia, N., Bramante, J., Cline, J. M., Curtin, D., McKeen, D., Morrissey, D. E., … & Zhang, Y. (2024). Dark matter candidates and searches. Canadian Journal of Physics.

Burbidge, G. R., & Burbidge, E. M. (1959). The Hercules Clusters of Nebulae. The Astrophysical Journal, 130, 629.

Caputo, R., Linden, T., Tomsick, J., Prescod-Weinstein, C., Meyer, M., Kierans, C., … & Kopp, J. (2019). Looking Under a Better Lamppost: MeV-scale Dark Matter Candidates. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.05845.

Carollo, M., de Zeeuw, T., van der Marel, R., Danziger, J., & Qian, E. (1995). Dark matter in elliptical galaxies. arXiv preprint astro-ph/9501046.

CMS collaboration. (2017). Search for supersymmetry in multijet events with missing transverse momentum in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.07781.

Corbelli, E., & Salucci, P. (2000). The extended rotation curve and the dark matter halo of M33. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 311(2), 441-447.

Dark matter | CERN. (2020). Home.cern. Retrieved 6 May 2020, from https://home.cern/science/physics/dark-matter

Faber, S. M., & Gallagher, J. S. (1979). Masses and mass-to-light ratios of galaxies. Annual review of astronomy and astrophysics, 17(1), 135-187.

Feng, J. L., Matchev, K. T., & Wilczek, F. (2000). Neutralino dark matter in focus point supersymmetry. Physics Letters B, 482(4), 388-399.

Freeman, K. C. (1970). On the disks of spiral and S0 galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal, 160, 811.

Garrett, K., & Duda, G. (2011). Dark matter: A primer. Advances in Astronomy, 2011.

Gott III, J. R., Gunnj, J. E., Schramm, D. N., & Tinsley, B. M. (1974). An unbound universe?.

Holmberg, E. (1940). On the Clustering Tendencies among the Nebulae. The Astrophysical Journal, 92, 200.

Holtzman, J. A. (1989). Microwave background anisotropies and large-scale structure in universes with cold dark matter, baryons, radiation, and massive and massless neutrinos. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 71, 1-24.

Jungman, G., Kamionkowski, M., & Griest, K. (1996). Supersymmetric dark matter. Physics Reports, 267(5-6), 195-373.

Kamionkowski, M. (1997). WIMP and axion dark matter. arXiv preprint hep-ph/9710467.

λCDM model Definition – Astrophysics II Key Term. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://fiveable.me/key-terms/astrophysics-ii/lcdm-model

Limber, D. N. (1962). Kinematics and Dynamics of Clusters of Galaxies. In Problems of extra-galactic research (Vol. 15, p. 239).

Milgrom, M. (1983). A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. The Astrophysical Journal, 270, 365-370.

Milgrom, M. (1983). A modification of the Newtonian dynamics-Implications for galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal, 270, 371-389.

Milgrom, M. (1983). A Modification of the Newtonian Dynamics-Implications for Galaxy Systems. The Astrophysical Journal, 270, 384.

Milgrom, M. (1989). Alternatives to dark matter. Comments on Astrophysics, 13, 215.

The Bullet Cluster (Milgrom). (2020). Web.archive.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020, from https://web.archive.org/web/20160721044735/http:/www.astro.umd.edu/~ssm/mond/moti_bullet.html

Milgrom, M. (2014). MOND theory. Canadian Journal of Physics, 93(2), 107-118.

Milgrom, M. (2020). MOND vs. dark matter in light of historical parallels. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics.

Natarajan, P., Chadayammuri, U., Jauzac, M., Richard, J., Kneib, J. P., Ebeling, H., … & Atek, H. (2017). Mapping substructure in the HST Frontier Fields cluster lenses and in cosmological simulations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 468(2), 1962-1980.

Navarro, J. F., Eke, V. R., & Frenk, C. S. (1996). The cores of dwarf galaxy haloes. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 283(3), L72-L78.

(N.d.). Retrieved from https://www.aps.org/apsnews/2005/07/february-1917-einsteins-biggest-blunder

Ostriker, J. P., Peebles, P. J. E., & Yahil, A. (1974). The size and mass of galaxies and the mass of the universe.

Peebles, P. J. E. (1982). Large-scale background temperature and mass fluctuations due to scale-invariant primeval perturbations.

Primack, J. R. (2001). Whatever happened to hot dark matter?. arXiv preprint astro-ph/0112336.

Refregier, A. (2003). Weak gravitational lensing by large-scale structure. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 41(1), 645-668.

Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., Clocchiatti, A., Diercks, A., Garnavich, P. M., … & Tonry11, J. (1998). Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. arXiv preprint astro-ph/9805201.

Roberts, B. M., Blewitt, G., Dailey, C., Murphy, M., Pospelov, M., Rollings, A., … & Derevianko, A. (2017). Search for domain wall dark matter with atomic clocks on board global positioning system satellites. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-9.

Roberts, M. S., & Rots, A. H. (1973). Comparison of rotation curves of different galaxy types. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 26, 483-485.

Rogstad, D. H., & Shostak, G. S. (1972). Gross properties of five Scd galaxies as determined from 21-centimeter observations. The Astrophysical Journal, 176, 315.

Rubin, V. C., & Ford Jr, W. K. (1970). Rotation of the Andromeda nebula from a spectroscopic survey of emission regions. The Astrophysical Journal, 159, 379.

Rubin, V. C., Ford Jr, W. K., & Thonnard, N. (1978). Extended rotation curves of high-luminosity spiral galaxies. IV-Systematic dynamical properties, SA through SC. The Astrophysical Journal, 225, L107-L111.

Rubin, V. C. (1979). Rotation curves of high-luminosity spiral galaxies and the rotation curve of our Galaxy. In Symposium-International Astronomical Union (Vol. 84, pp. 211-220). Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt, M. (1957). The distribution of mass in M 31. Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands, 14, 17.

Schwarzschild, M. (1954). Mass distribution and mass-luminosity ratio in galaxies. The Astronomical Journal, 59, 273.

Smith, S. (1936). The mass of the Virgo cluster. The Astrophysical Journal, 83, 23.

Strigari, L. E. (2013). Galactic searches for dark matter. Physics Reports, 531(1), 1-88.

Van de Hulst, H. C., Raimond, E., & Woerden, H. V. (1957). Rotation and density distribution of the Andromeda nebula derived from observations of the 21-cm line. Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands, 14, 1.

Wu, X. P., Chiueh, T., Fang, L. Z., & Xue, Y. J. (1998). A comparison of different cluster mass estimates: consistency or discrepancy?. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 301(3), 861-871.

Zwicky, F. (1933). The redshift of extragalactic nebulae. Helv. Phys. Acta, 6(110), 138.

Zwicky, F. (1937). On the Masses of Nebulae and of Clusters of Nebulae. The Astrophysical Journal, 86, 217.