Anyone who has spent much time addressing a lot of myths, misconceptions, and anti-science arguments has probably had the experience of some contrarian taking issue with his or her rebuttal to some common talking point on the grounds that it’s not the “real” issue people have with the topic at hand. It does occasionally happen that some skeptic spends an inordinate amount of time refuting an argument that literally nobody has put forward for a position, but I’m specifically referring to situations in which the rebuttal addresses claims or arguments that some people have actually made, but that the contrarian is implying either haven’t been made or shouldn’t be addressed, because they claim that it’s not the “real” argument. This is a form of No True Scotsman logical fallacy, and is a common tactic of people who reject well-supported scientific ideas for one reason or another. In some cases this may be due to the individual’s lack of exposure to the argument being addressed rather than an act of subterfuge, but it is problematic regardless of whether or not the interlocutor is sincere.

The dilemma is that there are usually many arguments for (and variations of) a particular position, so it’s not usually possible for someone to respond to every possible permutation of every argument that has ever been made against a particular idea (scientific or otherwise). The aforementioned tactic takes advantage of this by implying that the skeptic is attacking a strawman on the grounds that what they refuted was not the “real” main argument for their position. In comment sections on my page, I’ve referred to this as The One True ArgumentTM fallacy. It’s a deceptive way for the contrarian to move the goalpost while deflecting blame back onto the other person by accusing them of misrepresentation. The argument being addressed has been successfully refuted, but instead of acknowledging that, the interlocutor introduces a brand new argument (often just as flawed as the one that was just deconstructed), and accuses the person debunking it of either not understanding or not addressing The One True ArgumentTM.

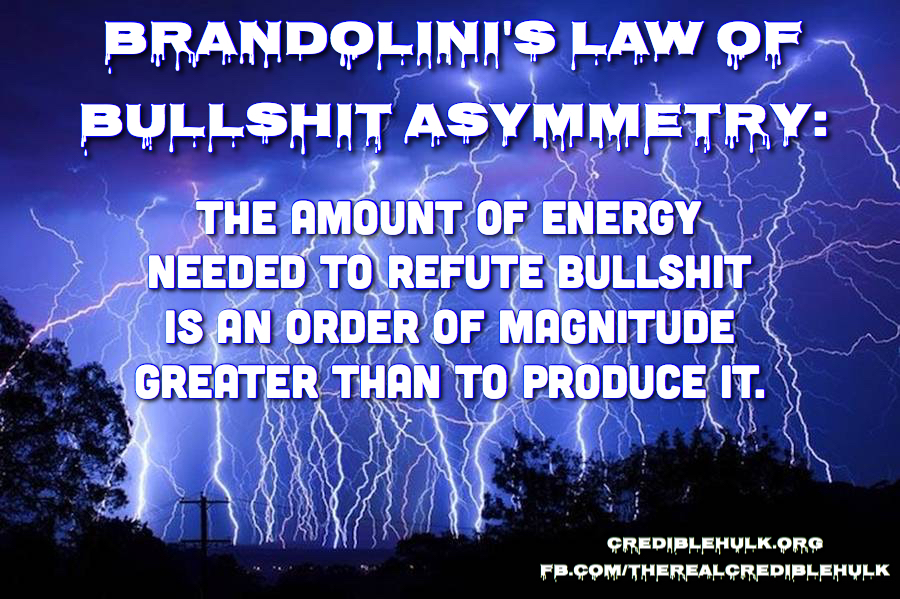

Some brands of science denial have brought this to the level of an integrative art form. If argument set A is refuted, they will cite argument set B as The One True ArgumentTM, but if argument set B is refuted, they will either cite argument set A or argument set C as The One True ArgumentTM. If argument sets A, B, and C are all refuted in a row, they’ll either bring out argument set D, or they will accuse the skeptic of relying on verbosity, and will attempt to characterize detailed rebuttals as some sort of vice or symptom of a weak argument (even though the skeptic is merely responding to the claimant’s arguments). I really wish I was making this up, but these are all techniques I’ve seen science deniers use in debates on social media or on their own blogs. Of course, the volume of the rebuttal cannot be helped due to what has come to be known as Brandolini’s Law AKA Brandolini’s Bullshit Asymmetry Principle (coined by Alberto Brandolini), which states that the amount of energy necessary to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.

The argumentation tactics of sophisticated science deniers and other pseudoscience proponents (or even the less sophisticated ones) could probably fill an entire book, but this is one that I haven’t seen many people address, and it comes up fairly often.

For example, many opponents of genetically engineered food crops claim that they are unsafe to eat, and that they are not tested. Often when someone takes the time to show that they are actually some of the most tested foods in the entire food supply, and that the weight of evidence from decades of research from scientists all across the world has converged on an International Scientific Consensus that the commercially available GE crops are at least as safe and nutritious as their closest conventional counterparts, the opponents will downplay it as not being the “real” issue. In some cases they will appeal to conspiracy theories or poorly done outlier studies that have been rejected by the scientific community, but in other instances they will invoke The One True ArgumentTM fallacy. They will claim that nobody is saying that GMOs are unsafe to eat, and that the problem is the overuse of pesticides that GMOs encourage, or that the problem is that the patents and terminator seeds allegedly permit corporations to sue farmers for accidental cross contamination and monopolize the food supply by prohibiting seed saving.

Of course, these arguments are similarly flawed. GMOs have actually helped reduce pesticide use: not increase it, (particularly insecticides) [1],[2],[3], and have coincided with a trend toward using much less toxic and environmentally persistent herbicides [4]. Plant patents have been common in non-GMO seeds too since the Plant Patent Act of 1930, terminator seeds were never brought to market, the popularity of seed saving had already greatly diminished several decades before the first GE crops, and there are still no documented cases of non-GMO farmers getting sued by GMO seed companies for accidental cross-contamination.

However, although the follow up arguments are similarly flawed, the fact is that many organizations absolutely are claiming that genetically engineered food crops are unsafe. I’m not going to give free traffic to promoters of pseudoscience if I can help it, but one need only to plug in the search terms “gmo + poison” or “gmo + unsafe” to see a plethora of less-than-reputable websites claiming precisely that. The point is that it’s dishonest to pretend that the person rebutting such claims isn’t addressing the “real” contention, because there is no one single contention, and the notion that the foods are unsafe is a very common one.

Another example occurred just the other day on my page. I posted a graphic depicting some data showing how effective vaccines have been at mitigating certain infectious diseases. A commentator responded as shown here:

I responded thusly:

Putting aside the fact that information on vaccine ingredients is easy to obtain (they are laid out in vaccine packaging inserts), and the fact that increasing life expectancy and population numbers suggest that, if there is any nefarious plot to depopulate the planet, the perpetrators have been spectacularly unsuccessful so far, the point is that this exemplifies The One True ArgumentTM tactic.

Putting aside the fact that information on vaccine ingredients is easy to obtain (they are laid out in vaccine packaging inserts), and the fact that increasing life expectancy and population numbers suggest that, if there is any nefarious plot to depopulate the planet, the perpetrators have been spectacularly unsuccessful so far, the point is that this exemplifies The One True ArgumentTM tactic.

Another common example is when scientists meticulously lay out the arguments and evidence for how we know that global warming and/or climate change are occurring. There are many common contrarian responses to this, some of which employ the One True Argument fallacy, such as when the contrarian claims that nobody actually rejects the claim that the change is occurring, bur rather they doubt that human actions have played any significant role in it.

Of course, the follow up claim is similarly flawed, since we know that climate changes not by magic but rather when acted upon by physical causes (called forcings), none of which are capable of accounting for the current trend without the inclusion of anthropogenically caused increases in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases such as CO2. This is because most of the other important forcings have either not changed much in the last few decades, or have been moving in the opposite direction of the trend (cooling rather than warming). I’ve explained how solar cycles, continental arrangement, albedo, Milankovitch cycles, volcanism, and meteorite impacts can affect the climate with hundreds of citations from credible scientific journals here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

In this instance, although it has become more common than in the past for climate science contrarians to accept the conclusion that climate has been changing but reject human causation, there are still plenty who argue that the warming trend itself is grand hoax, and that NASA, NOAA, (and virtually every other scientific organization on the planet) has deliberately manipulated the data to make money. If you doubt this, all you need to do is enter “global warming + hoax + fudged data” into your favorite search engine to see an endless list of webmasters making this claim. In fact, in one study, the position that “it’s not happening” at all was the single most common one expressed in op-ed pieces by climate science contrarians between 2007 – 2010 [10]. Their abundance even increased towards the end of that time period, so it’s flat out untrue that the push-back against the science has centered only on human causation and/or the eventual severity of the problem.

The truth is that there was never anything nefarious going on with the temperature data adjustments. Similar adjustments are performed on data in most scientific fields. They were completely legitimate and scientifically justified. There have even been additional studies in which the assumptions and reasoning behind the ways in which the data was adjusted have been scrutinized and compared to data from reference networks, and the same procedures produced readings that were MORE accurate than the raw non-adjusted data: not less [5],[6],[7].[8].[9]. This is nicely explained here, but I digress; the main point here is not just that the follow-up arguments tend to be similarly flawed, but rather that this technique could in principle be used indefinitely to move the goal posts ad infinitum.

It’s easy to see that this also forces a strategic decision on the part of the skeptic or science advocate. Do you nail them down on their use of this tactic? Do you respond to the follow-up argument they’ve presented as the “real” issue? Do you do both? If so, are there any strategic disadvantages to doing both? Would it make the response excessively long? If so, does that matter? If so, how much can it be compressed by improved concision without sacrificing accuracy and/or important details? Disingenuous argumentative tactics like these put the contrarian’s opponents in a position where he or she has to make these kinds of strategic decisions rather than simply focusing on the veracity of specific claims.

As I alluded to earlier, this is not a free license to construct actual strawmen of other people’s positions and ignore their explanations when they attempt to clarify their arguments and their conclusions, because people do that too, and that’s no good either. But the One True ArgumentTM fallacy refers specifically to when a refutation to a common argument is mischaracterized as a strawman as a means of introducing a different argument while trying to construe it as the skeptic’s fault for addressing the argument they addressed instead of some other one. It’s dishonest, it’s based on bad reasoning, you shouldn’t use it, and you should point it out when others do.

References:

[1] Brookes, G., & Barfoot, P. (2017). Environmental impacts of genetically modified (GM) crop use 1996–2015: impacts on pesticide use and carbon emissions. GM crops & food, (just-accepted), 00-00.

[2] Klümper, W., & Qaim, M. (2014). A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops. PloS one, 9(11), e111629.

[3] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. National Academies Press (pg. 117-119).

[4] Kniss, A. R. (2017). Long-term trends in the intensity and relative toxicity of herbicide use. Nature communications, 8, 14865.

[5] Jones, P. D., & Moberg, A. (2003). Hemispheric and large-scale surface air temperature variations: An extensive revision and an update to 2001. Journal of Climate, 16(2), 206-223.

[6] Brohan, P., Kennedy, J. J., Harris, I., Tett, S. F., & Jones, P. D. (2006). Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: A new data set from 1850. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 111(D12).

[7] Jones, P. D., Lister, D. H., Osborn, T. J., Harpham, C., Salmon, M., & Morice, C. P. (2012). Hemispheric and large‐scale land‐surface air temperature variations: An extensive revision and an update to 2010. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 117(D5).

[8] Hausfather, Z., Menne, M. J., Williams, C. N., Masters, T., Broberg, R., & Jones, D. (2013). Quantifying the effect of urbanization on US Historical Climatology Network temperature records. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 118(2), 481-494.

[9] Hausfather, Z., Cowtan, K., Menne, M. J., & Williams, C. N. (2016). Evaluating the impact of US Historical Climatology Network homogenization using the US Climate Reference Network. Geophysical Research Letters.

[10] Elsasser, S. W., & Dunlap, R. E. (2013). Leading voices in the denier choir: Conservative columnists’ dismissal of global warming and denigration of climate science. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(6), 754-776.

4 Comments

Rob · May 2, 2017 at 12:42 pm

Thank you! I have often run into the “well, climate change could be caused by variations in orbit!”

The problem I find is that when they resort to conspiracy theories (vaccines are population control!) or attacks on the integrity of the researchers (climate data is fudged!), the argument is effectively over.

I used to think that this is because they’re arguing in bad faith – they’re just bringing up the conspiracy to try and win – but in some cases I now think that they just simply don’t trust scientific authority, and cannot be persuaded to.

But, I’ve also found that leaving the argument at this point is useful, because (of my friends who argue in good faith), at this point they go home and read more, and start to think more.

Thanks for putting words to this phenomenon for me!

Credible Hulk · May 6, 2017 at 12:07 am

You bring up an important observation, Rob. Sometimes it’s tempting to just keep piling on the facts and refuting the follow-up arguments just because the person brought the new ones up. But sometimes it makes more sense to plant a seed and just allow them time to process it. That may work better than just deconstructing argument after flawed argument until one gets too tired (assuming there was ever any hope of reaching the person at all).

Sceptom · May 12, 2017 at 3:44 pm

I’ve seen this tactic more commonly referred to as “moving the goal posts” than “the one true argument”. Still as deceptive though.

Credible Hulk · August 9, 2017 at 3:36 am

It definitely includes a moving of the goalpost component, but that’s just one component of what I’m attempting to describe. It’s a composite of more than one fallacy. It combines moving the goalpost with a no true Scotsman fallacy in a way that is common enough that I decided it deserved to be addressed on its own. The name is my own. If people don’t like the name and prefer to describe it as a combo of other known fallacies, then that’s fair enough. I just wanted to address it because that particular combo occurs so often on my FB page.

Comments are closed.