A chemical’s properties are not affected by whether it was made by God, Mother Nature, evolution, or a chemist in a lab coat.

There’s a certain irony to drinking a soy latte from a BPA-free mug, but that’s not something the chemophobic fear squad seems to understand. This fear-mongering crowd would have you believe that synthetic endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are going to be the downfall of civilization as we know it (I admit, that’s hyperbolic, but so are many of their exaggerated claims). However, in a truly perfect example of inconsistent application of the precautionary principle and selective consideration of data and data gaps, they completely overlook the potential risks of phytoestrogens, naturally occurring endocrine-disrupting chemicals found in soy and other common foods.

Phytoestrogens are of particular concern because of the increased consumption of phytoestrogen-containing food. Sales of soy-based food products (tofu, tempeh, edamame, soy “milk”, soy “yogurt”, soy-based baby formula) have grown substantially since the late 1990s. Other sources of phytoestrogens include grapes and red wine, citrus fruits and juices, parsley, celery, pepper, kale, broccoli, onions, tomatoes, lettuce, apples, chocolate, green tea, beans, apricots, cherries, berries, spinach, and flax seed.

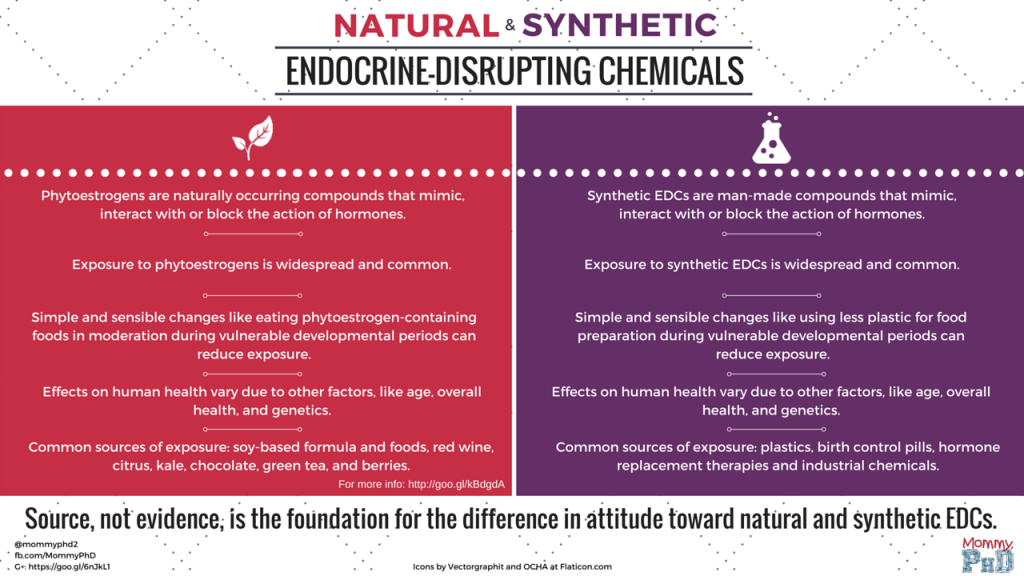

Data suggest that the exposure to EDCs from natural dietary sources may be higher than exposure to synthetic EDCs although this is a difficult comparison to make conclusively. Epidemiological studies of the health effects of both show mixed, complicated (i.e. confounded by associated factors), and mostly small results. Despite this nuance, we tend to view natural EDCs favorably, and synthetic EDCs unfavorably, despite having similar chemical properties. Source, not evidence, is the foundation for the difference in attitude toward natural and synthetic EDCs.

Now, this is not meant to make you afraid of eating soy, kale, berries and all these other foods, or of using your shampoo. I point this out to draw attention to the fact that that we tolerate a lot of risk in our lives and that exposure and risk are unavoidable parts of life. A simplistic dichotomy between the hazards of synthetic exposures and safety of natural exposures is often not based on evidence. There is truly no such thing as a risk-free, exposure-free life, even with so-called “all-natural” products. However, there are some simple and easy steps to reduce exposures if you are concerned, like avoiding soy-based products and use less plastic in food preparation and storage during sensitive developmental periods.

Reducing and mitigating risks where it is feasible to do so is reasonable, but it is often not a simple undertaking. For example, a recommendation to completely avoid phytoestrogen containing food would be misguided as evidence consistently shows that, despite concerns about exposure to phytoestrogens at certain times in life, a diet rich in a wide variety of fruits and vegetables produces a net benefit for health.

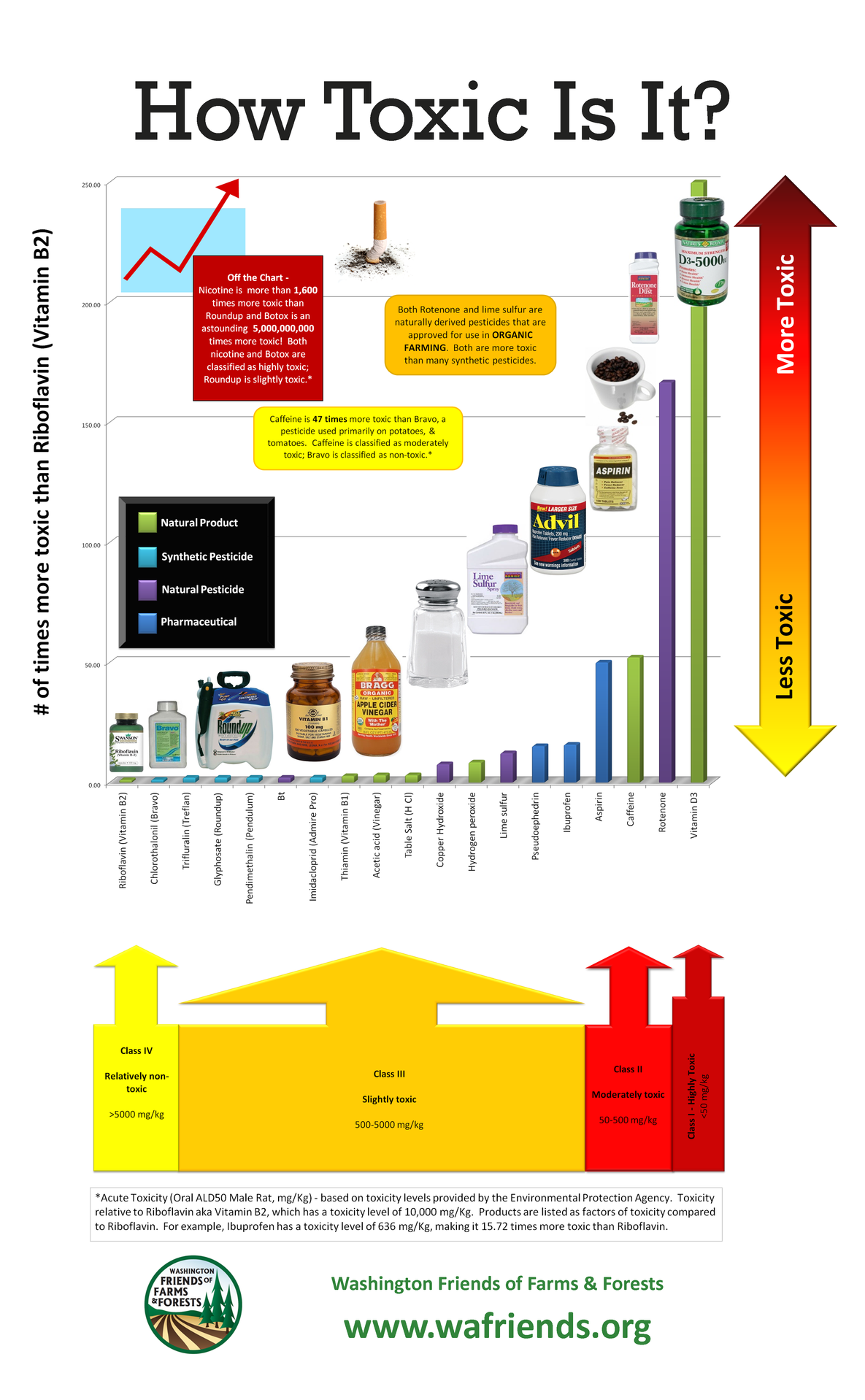

The similarities between natural and synthetic chemicals are often overlooked as we fall victim to our assumptions that natural is good and synthetic is bad. A chemical’s properties are not affected by how it was produced. Synthetic chemicals that have a biological effect are able to do so because they are able to mimic or interact with systems that exist in nature. Chemistry, not source, determines how a chemical acts in a biological system.

From a 2010 review, “The pros and cons of phytoestrogens”:

Phytoestrogens are intriguing because, although they behave similarly to numerous synthetic compounds in laboratory models of endocrine disruption, society embraces these compounds at the same time it rejects, often with vigor, use of synthetic endocrine disruptors in household products. Thus, phytoestrogens both expand our view of environmental endocrine disruptors and propound that the source of the compound in question can influence the direction and interpretation of research and available data. While the potentially beneficial effects of phytoestrogen consumption have been eagerly pursued, and frequently overstated, the potentially adverse effects of these compounds are likely underappreciated. The opposite situation exists for synthetic endocrine disruptors, most of which have lower binding affinities for classical ERs than any of the phytoestrogens but can sometimes produce similar biological effects. (emphasis mine)

In interpreting information about health effects of chemicals, wherever they come from, we must be aware of our biases in favor of the natural and against the synthetic to ensure that we analyze data objectively. Only when we consider evidence without bias can we arrive at sound recommendations and regulations.

3 Comments

Alice · March 29, 2016 at 11:22 pm

This makes sense, but the levels of EDCs that accumulate in the water from pollutants are much higher than has ever been caused by “natural” sources.

Credible Hulk · May 14, 2016 at 10:24 pm

Citation?

Myron Pyzyk · March 30, 2016 at 7:59 pm

Well said. As my training is in clinical nutrition, there is one other example to add to what you said about the body not differentiating synthetic and natural. It involves calories as well as the over exaggeration by natural food products on what the source of those calories should be. It’s mostly about input and output when it comes to calories and nowadays. There’s a whole lot more input going on nowadays than is necessary for our energy output hence why excessive weight gain & obesity is such a huge problem.

Comments are closed.